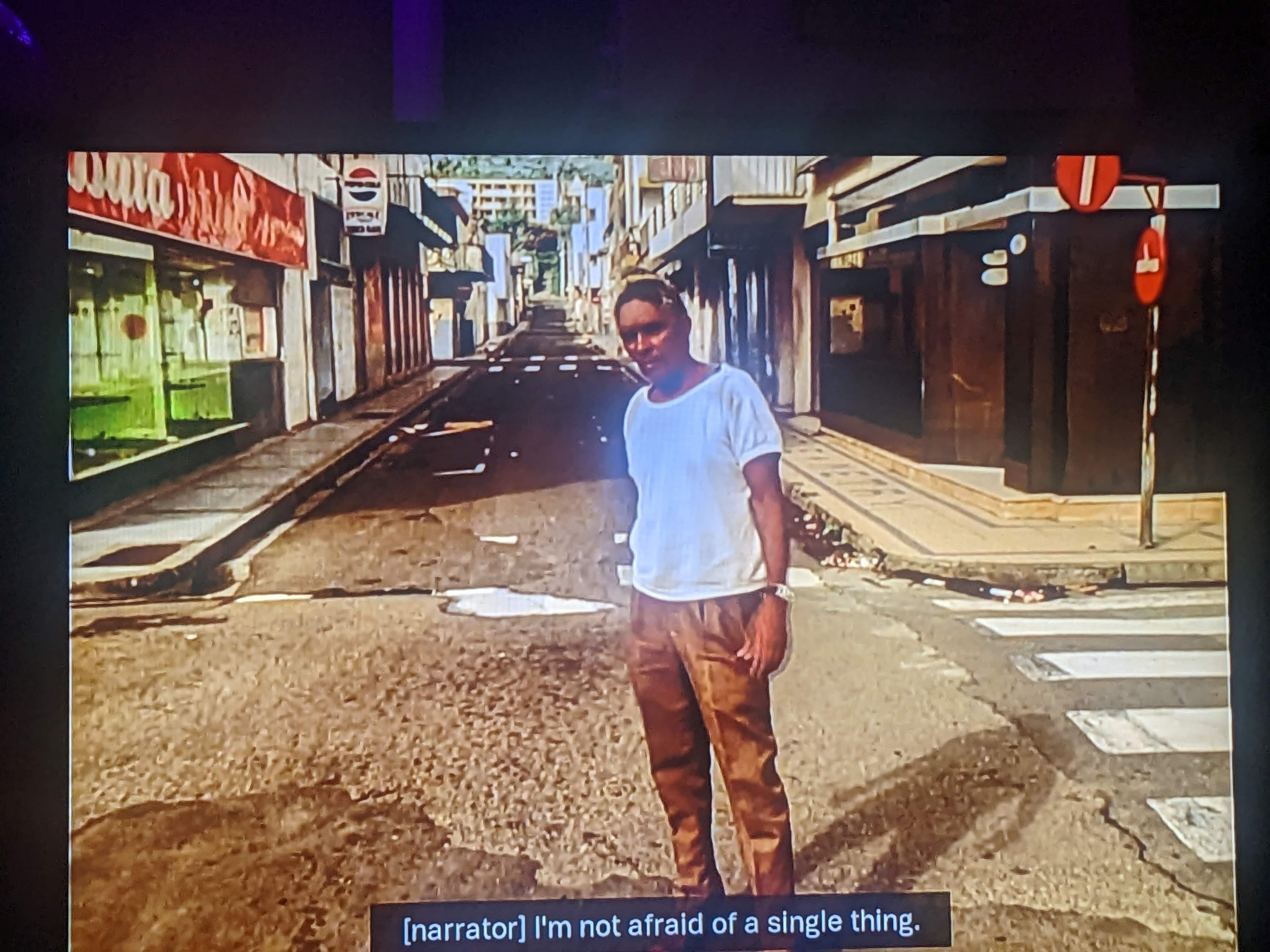

In 1976, 75,000 people fled the whole southern region of the island nation of Guadaloupe, and Werner Herzog showed up with a film crew to find the one man who refused to be evacuated. The island may have been their gravestone, with the man’s words as their epitaph:

“Like life, death is forever. I haven’t the slightest fear. God takes everyone to his bosom, he has ordained this for us. Why should I go? Death waits forever. I am not afraid of dying. Sure we are on a powder keg, aren’t all of us… it is God’s will. I’m at peace with myself, with what’s inside me. I am poor, I have nothing. Where should I go?”

Life’s gamble, for those who live in poverty, is thus defined. Herzog says at that point in La Soufrière: Waiting for an Inevitable Catastrophe, that it is not the volcano that interests him the most, but the treatment of Black people on the island.

38 years later, in Into the Inferno, Herzog pivots away from the material point of La Soufrière. Herzog and volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer take us to visit another type of gamble for life – only slightly less death defying – atop another volcano. We follow the search for the remains of hominids with an archaeological dig crew. At Erta Ale, the “Gateway to Hell”, ancestors came to the volcanic region to collect obsidian likely as a tool. A fun fact is dropped here, obsidian was used recently in the medical field as a preferable instrument for eye surgeries, as it is the blades are sharper and finer than steel. The fossilized and crushed bones of the ancestors are entombed in the volcanic ash and silt. The gamble is to find what bones belong to what or whom, atop the 6 million year old Middle Awash valley (a better bet when you have an expert fossil hunter on the team). On a site of supposed destruction, the cycle of creative force awaits mankind to understand itself more deeply (with humankind so lucky to have a Herzog to bring understanding to the masses!).

Human relationships with the volatility of the Earth have defined human existence for epochs. Humans as a species gamble with volatility every time we have settled, but living through the climate chaos of the Capitolocene is creating a whole new level of predicament.

I am writing this during a heatwave, where many parts of California, an already hot region, are expecting records to be shattered. The effect on an already drought-stricken corridor is expected to be disastrous. The Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys see settlements suffering from the boom and bust of industrialized agriculture, dozens of crowded mega-prisons that California’s colonial legacy filled up with dispossessed, in a region that has seen a crisis of homelessness due to the profit engineering of a speculative housing market. Pivoting back to Herzog’s earlier social point, these catastrophes have historically targeted communities of Black, Indigenous, and immigrant people, and those who work yet remain in poverty.

We all seem to know that climate chaos will have increasingly inevitably catastrophic social consequences unless a large-scale change in fossil fuel reliance happens, the possibility of which seems dwindles due to the pathetic impotence of global decision makers. The next best solution for the poor has been evacuation, creating a global refugee bottleneck at the borders of whiter nations. The so-called Golden State, formerly known for gilted minerals but the “gold” today is the dry yellowed grass covering formerly lush hills, has been an utter success for the rich, and catastrophe for the poor.

Living in the Capitolocene should not mean inevitable catastrophes, when this era of the Anthropocene could mean something objectively better, an era where each man, woman, and child could achieve their highest human potential in art, science, ideas, love. As long as the elites in power keep gambling with life, life will feel like a gamble for the poor. Can humankind get out from under the boot of those who gamble with life? Can people and the planet enact a relationship with each other and the planet that recognizes true dignity and agency?

In Inferno, Mael Moses, Chief of the Endu Village on the border of a volcano in Vanuatu, shares the history and spirituality that lives in their volcano. In dance processions, the people engage to please the volcanic spirits. It was the perspective of locals that tourists were the cause of previous volcano eruptions: the volcano demon was looking at the people of the tribe and it recognized them. Yet when it looked upon faces of tourists, perhaps people who did not honor the spirit in return, the volcano demon became angry and erupted. Is recognizing and respecting the unknown, instead of imposing order upon it, the way to maintain dignity and agency of that entity?

The “trigger” and destructive potential of volcanoes is still near impossible to reliably predict. The work of Kattja and Maurice Krafft, briefly mentioned in Inferno, has advanced global understandings of volcanoes. The Fire of Love is an ode to the volcanologist couple whose respect for these volcanoes defined their lives and deaths. In the film we see dozens of lush borders of calderas, as volcanic ash offers rich, fertile soil for new life to grow. After spanning the globe studying “friendly” red volcanoes, their work turned towards “monster, killer” gray volcanoes. While studying Mt. Unzen volcano in Japan, they were killed by a pyroclastic current that swept over them. While remains were not found, some objects that belonged to both were found next to each other. The work of this couple/team expanded humankind’s knowledge of the interrelation of the unpredictable, and went towards advising in evacuations that likely saved tens of thousands of people, most immediately was the evacuations prior to the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines, just months after Unzen.

In Fire of Love, Maurice Krafft says that to box volcanoes into categories would be archaic scientific thinking, stripping each volcano of its unique personality and individual dignity. The magical side of volcanology in Inferno takes different forms on different islands, reflecting each volcano and regions various personalities. Offerings, reconciliations, and rituals take several days and involve a large swath of people of each respective society. As each volcano is connected beneath the surface of the earth, there is not a single person there who is unconnected to their local volcano.

“There’s no permanence to what we are doing – human beings, art, science… our life can only survive because volcanoes create the atmosphere that we breathe,” Oppenheimer says. To humbly live on this planet, to surrender to living in a volatile place, means respecting the impermanence of ourselves and each other, in cycles of creativity that abound through and beyond us.

I think of the masses of people in the web of life: all the people who make the stuff of this world and make life livable. Today the destructive forces of extractive profit and order imposed over nature simultaneously double-down and wane. The creative potential of people dispossessed by capitalism will continue like the magma beneath volcanoes that has always been moving, finding, and creating pathways beneath and through the crust. Perhaps it is a matter of faith for me: the imperceptible tremors propel me. I believe in the inevitable eruption over the supposed current order of society, where creative lava will flow anew for seeds to cultivate another epoch of dignified, interconnected life.

P.S. HAPPY WORLD HERZOG DAY!!!