Successful social realism feels like a rare treat these days. Some contemporary mainstream films might contain interesting commentary on a government or culture, but class-consciousness slips away in favor of a stock hero’s quest or feel-good twists. It’s often a question of access and representation – who gets to tell the story about who?

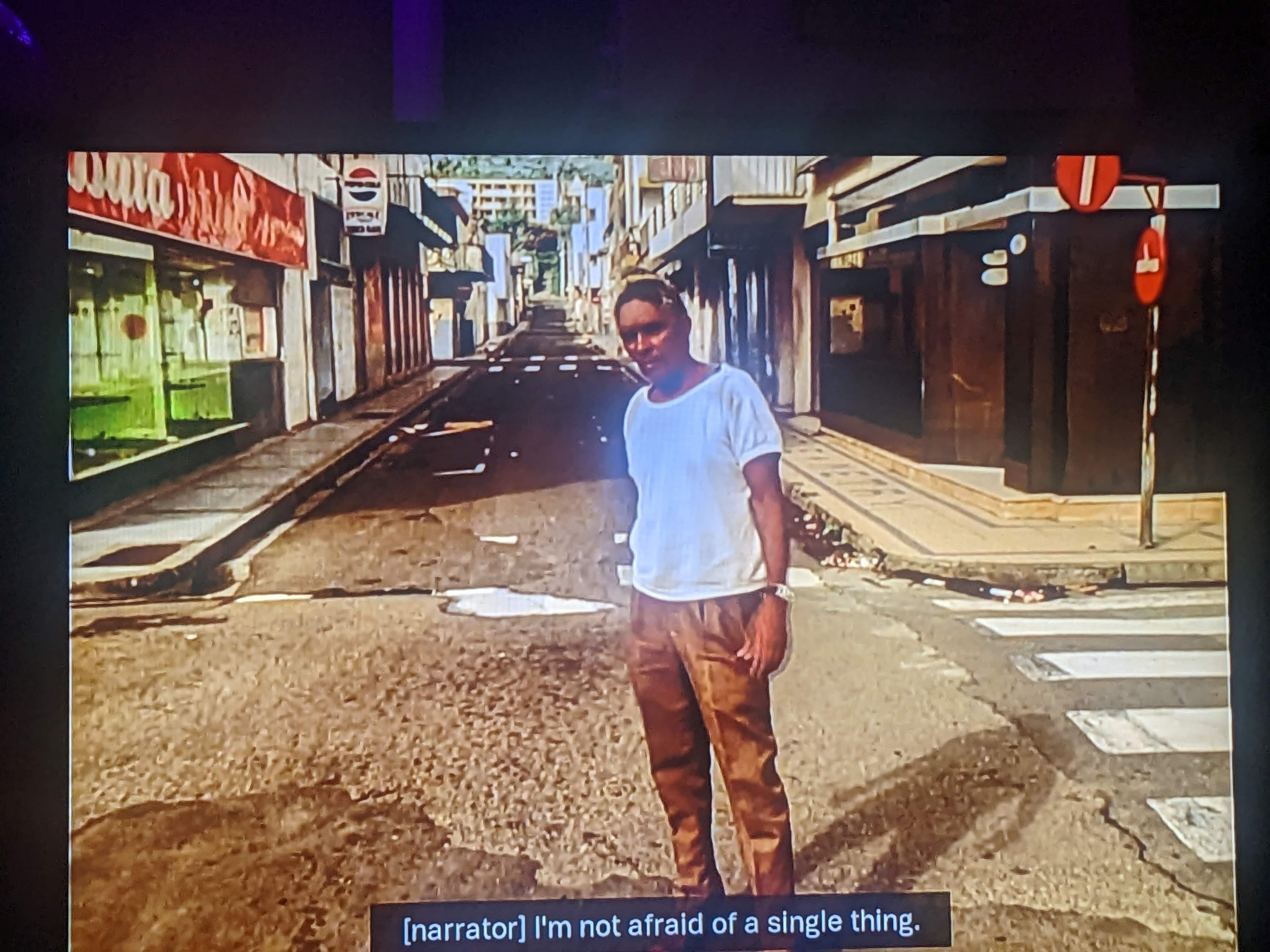

One of the most intense realist films of the 2000s is Samson and Delilah, a love story about two teenagers in an Aboriginal reservation. Unfolding nearly completely non-verbally, the film follows the repetitive days of normal life for the teen, until an event forces them to run away together. The film was the first feature of Warwick Thornton, a Kaytetye Aboriginal director (a great filmography is now on Criterion). Thornton shows that the persistence of Samson, and the patience of Delilah are traits quickly dismissed and discarded by white society. But while whiteness makes up part of the landscape the characters inhabit, the central force of the film is the world the characters create. It feels that such an intimate portrait might not be possible made by a white man, for an inherent lack of understanding. As a non-Australian, non-indigenous viewer, there’s likely more I won’t understand from even viewing, with cultural norms lost in translation.

Schisms between sophisticated Aboriginal modes of expression and communication, and white man’s demand for precise pronouncements and adherence to convention is a theme in Where the Green Ants Dream. The film primarily follows a white geologist at a mining company whose project is interrupted by a large group of Aboriginal people. We see groups of steady elders standing in front of bulldozers, whose white drivers who become increasingly unhinged in the obviously sweltering heat. We discover the project is interrupting – blasting through – the dreamtime origin of the green ants. Throughout the film, the communication breakdowns about the importance of this precise location are both comedic device, source of frustration, and pivot point for understanding the actions and worldview of the Aboriginal community.

Among many Aboriginal cultures, the dreamtime is when the world was made by the ancestors. I lived in Australia briefly and had a brief glimpse into aspects of Aboriginal country and cosmology. For me, it was a formative experience: education in the so-called United States is focused more on the colonizers and waves of settlers, rather than on the land and original peoples. Learning of dreaming and the dreamtime was fundamentally shattering to the conventions I learned while socialized in a white man’s education system. Thus, I identify with Herzog’s fascination that turned into deep respect for the indigenous cultures and perspectives featured in the film. Where the Green Ants Dream caused quite the stir, angering some white Australian audiences and the film only had a limited release there. But what is the point, when a white man is mad at a white man, but they still push down the indigenous perspective? After centuries of genocide, forced relocation, and erasure, can white folks just step aside so indigenous folks can represent themselves without getting pushed down?

In so-called California where I live, recent debate over a famous white fella environmentalist John Muir. During a period of heavy logging and forest clearing by the US Forest Service, John Muir’s writings and activism about “magnificent un-peopled expanses of forest” stopped clear-cuts and helped create national parks. While seen as a hero to white environmentalists, he is also viewed as a “symbol of white settler appropriation of the sanctity of land,” as science-fiction writer Kim Stanley Anderson shares in this interview. Indigenous peoples were inhabitants and stewards of the land for generations before Muir. How can we all be a part of society’s evolution to appreciate how white fellas like Herzog, and Bruce Chatwin, represent indigeneity but keep working to deeply incorporate truer histories into our current systems and practices, (especially when all the top content in searches are white folks?!)?

Material support like subscribing to indigenous-run media and art, and supporting the land back movement by paying tax to indigenous owners of the local land, and featuring artists and thinkers who are indigenous.

In that spirit, while not enough, here a few indigenous media and Aboriginal artists resources that I’m certainly seeking to learn and follow:

- One of the most prolific Aboriginal artists of the contemporary era: Emily Kame Kngwarreye

- All My Relations podcast

- The Red Nation organization

- Ohlone land, (the land I am on)

Any media any readers wish to share – please do in the comments!

And p.s.: I couldn’t wrap up this post without a shout out to the green ants: here is also a video of David Attenborough showing how they build their nests!